Esophageal Cancer in the United States Social Class Peer Reviewed

Review Article on Global GI Malignancies

Esophageal cancer: the rise of adenocarcinoma over squamous prison cell carcinoma in the Asian belt

Introduction

The incidence of esophageal cancers worldwide has been changing over the twentieth century, with rates of adenocarcinoma in comparison to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). SCC historically has been the predominate tumour encompassing 90% to 95% of all esophageal cancers. All the same, the transition from SCC to adenocarcinoma (AC) has been noted by many epidemiological serial and has been shown since the mid 1990's (1). This finding was initially observed in Western countries, with more recent increases in some Eastern countries as well every bit AC now accounts for 50% to lxxx% of esophageal cancer cases. In the United States, esophageal AC is the most predominant histology (2). This shift has led to much contend regarding the etiology of the disease, as well as the therapeutic options available for a malignancy with such rapid growth and high mortality with a 5-year survival of 15–20% at best. Common chance factors are shared between the two classifications; however, characteristics accept been identified that distinctly divide them. Although the increase is about notable in Western and high human evolution index (HDI) countries, the burden can too exist recognized in the esophageal cancer "hotspots." The population comprising the "Asian esophageal cancer belt" represents more 50% of all esophageal cancer cases worldwide, which allows for a big population size along with a broader array of "hotspots" that are easily compared. Although the vast bulk of these esophageal cancers are due to SCC, nosotros hypothesize that AC is an emerging hidden issue. In this review we analyzed trends inside China that could be contributing to the changing histological patterns of esophageal cancer. Specifically, the analysis of trends and contributing factors were evaluated with the ultimate goal of aiding the development of health care policies for screening and prevention to let command measures in the hereafter. Screening high-risk populations with endoscopy has shown to be beneficial, however, a set of global guidelines still needs to be established to ascertain who should exist chosen for the screening procedure.

Squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus

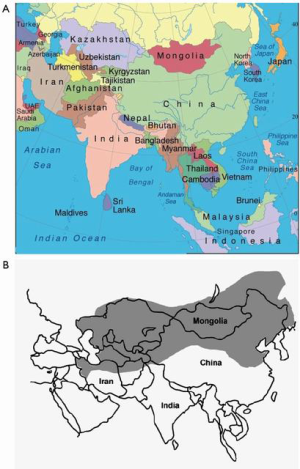

Esophageal SCC is predominant in the esophageal cancer "Asian belt" (Figure 1), including Northern Iran, Central Asia, and North-Cardinal China with an incidence estimated as high equally 100/100,000 annually (3). In western countries, including the USA, the incidence of esophageal SCC has been declining over the last several decades, and esophageal AC at present predominates (four). Although the general trend in the Usa is from esophageal SCC to Ac, this is disproportionate among all population subgroups in the United states of america; African American males are vii times more likely be diagnosed with esophageal SCC than esophageal AC, and US whites are 4 times more than probable to be diagnosed with esophageal AC than SCC (five). Although most Western societies take the same reduction in esophageal SCC equally the Usa, it is noted that SCC incidence rates are predicted to remain constant in areas such as the Great britain and Australia (6). Adventure factors for esophageal SCC include smoking and alcohol utilise, diet and nutrition, and HPV. Changes in smoking and booze usage in Western countries has decreased the incidence of esophageal SCC, but worldwide esophageal SCC remains a major health business organization.

Effigy ane The Central Asian Esophageal Cancer Chugalug extending from Islamic republic of iran to Cathay. Including countries and regions, such as Turkmenistan, Mongolia, Tajikstan, Bangladesh, Turkey, Islamic republic of iran, north-primal Mainland china. The Asian Esophageal Cancer Belt accounts for more than fifty% of all esophageal cancers worldwide. (A) Geographic reference with labeled countries (B) Geographical boundaries of the Asian Esophageal Belt.

Smoking and alcohol

Smoking has been known to exist a causal run a risk factor for esophageal SCC for many years now, increasing the risk 3–seven-fold in current smokers (7-nine). Smoking cigars and pipes take also been shown to increment the gamble of esophageal SCC, although to a lesser degree than cigarettes (10,11). Changes in smoking patterns, especially in Western countries, is believed to contribute to the reject in incidence of esophageal SCC (12). Alcohol consumption has also been shown to increment rates of esophageal SCC independently (13,xiv), and synergistically with tobacco consumption (15). Alcohol consumption in excessive amounts (>3 drinks per day) increases cancer hazard 3–5-fold, regardless of the blazon of alcohol (7,xvi). Even pocket-sized quantities of booze consumption of less than ten g/solar day, which correlates to 1 pocket-sized glass of wine, have been shown to increase esophageal SCC risk (17). In general the incidence of esophageal SCC is decreasing in the US. Nonetheless, it is even so 7 times more frequent in African Americans in the US, probable due to alcohol and tobacco use patterns (16,18,19). In 2016 a case control observational written report including 703 patients with SCC did evidence an increased risk of esophageal cancer with 2d-paw smoke in a dose dependent manner (20). In terms of second paw smoke and the associated chance of esophageal cancer, further studies are needed to determine if there is an associated risk.

Nutrition and nutrition

There are many associations between diet, hot beverages, and nutritional deficiencies that have been implicated with esophageal SCC. Diets high in pickled vegetables and N-nitrosamines are normally found in China and Eastern countries and accept been linked to esophageal SCC (16,21,22). Maté, a tea consumed either hot or common cold, contains polycyclic effluvious hydrocarbons, a known carcinogen. Maté is heavily consumed in South America where there is a high incidence of esophageal SCC (16). Certain hot beverages and prepared nutrient have also been hypothesized to be associated with esophageal SCC, idea to be due to thermal injury (23). Several studies have also shown that diets deficient in fruits and vegetables, zinc, selenium and vitamins are also associated with increased rates of esophageal SCC (16,24-26). Nutritional deficiencies are oft seen with booze employ and likely contribute to the increased rates of esophageal SCC in booze users. Betel nuts are the seeds of the fruit of the areca palm, which grows in the tropical Pacific, Southeast and South Asia, and parts of east Africa. It is very popular in areas such as Taiwan and Bharat, and has addictive backdrop due to the energy boost information technology produces. The clan betwixt betel nut and esophageal cancer has been in question for many years due to the high incidence of SCC in the areas where it is popular. In 2012 a meta-analysis of instance-command studies (2,836 cases; 9,553 controls) was done that showed betel nut chewing independently was associated with an increased hazard of SCC. All the same, when combined with tobacco smoking the chance increased essentially (27).

Human papilloma virus (HPV) related to esophageal cancer

Human being papilloma virus is a DNA virus well associated with SCC of the cervix, penis, oropharynx and anus. It tin also affect the esophagus similarly due to the squamous histological similarities as these other locations. Virus subtypes HPV16 and HPV18 are the oncogenic subtypes associated with cervical cancer, however, the association between HPV and esophageal SCC has not been well established (28). Studies investigating HPV in esophageal SCC found the virus in tumor cells ranging from 0–seventy% (29). Other studies, yet, did not notice HPV Deoxyribonucleic acid integrated into the tumor genome (xxx). A contempo article did identify a three times higher incidence of esophageal cancer in HPV positive individuals. In terms of prognosis of esophageal cancer due to HPV infection, Guo et al. performed a meta-analysis of 1184 cases to decide the associated progression of esophageal cancer (31). They were unable to show that at that place was any prognostic utility of the virus and its contributing factors. This assay was limited past the degree of heterogeneity in the HPV subtypes. Of the studies that were included in the meta-assay, but one was able to testify a practiced survival prognosis among HPV positive patients with esophageal SCC. The HPV vaccine is unlikely to take a significant result on rates of esophageal SCC worldwide since vaccination is typically performed in western countries. Further piece of work is required to more clearly identify the link between HPV and certain types of ESCC (32).

Squamous cell carcinoma in People's republic of china

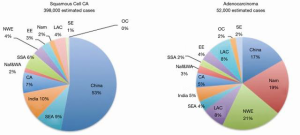

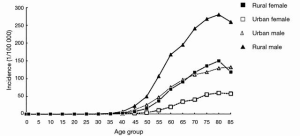

In 2012, at that place was estimated to exist 398,000 global cases of SCC, with the Asian belt comprising over seventy pct of the global total. Although esophageal cancer is decreasing in Mainland china over the terminal few decades, it is responsible for over 50% of all esophageal cancers. Figure 2 quantifies the global burden of esophageal cancer by histological blazon (33). Further studies have been underway in China to identify the major risk factors of the disease. Other studies reported a higher incidence in rural areas and men, with rates in rural areas double that of urban (34). This about probable is related to socioeconomic status and lifestyle with mutual take a chance factors similar those discussed previously. Figure 3 shows the incidence of esophageal cancer in both sexes and their state of residence in Red china.

Figure ii Prc represents 53% and 18% of global esophageal SCC and Air-conditioning respectively. Regional distribution of estimated esophageal cancer cases by histological subtype in 2012. CA, Central Asia; EE, Eastern Europe; LAC, Central & Southern America and Caribbean; NAm, Northern America; NAf & WA, Northern Africa/Western Asia; NWE, N Western Europe; OC, Oceania; SE, Southern Europe; Bounding main, South-Eastern asia; SSA, Sub-Saharan Africa.

Effigy 3 2011 age‐specific esophageal cancer incidence in Prc. Adapted from (34). Urban male and rural female person incidence rates of esophageal cancer are comparable. Similarities in their lifestyle, such as obesity, could exist associated.

Rise of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus

Over the past iv decades, the frequency of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, esophagogastric junction (EGJ), and gastric cardia has been increasing dramatically (35). The rising trend was first noted in Western countries with it surpassing SCC in the United States; however, recently increases have been noted in Eastern countries equally well. This has led to more focus on the etiology backside development of esophageal adenocarcinoma, as well every bit the adventure factors associated with its increasing frequency.

Adenocarcinoma arises from intestinal type cells (transition of squamous to abdominal blazon histology) and is more than frequently located in the lower third of the esophagus. Barrett's esophagus and chronic gastroesophageal reflux illness are the main chance factors associated with its pathology, with Barrett'due south esophagus associated with a 30 to 125-fold increment in esophageal adenocarcinoma (36). Barrett's metaplasia results from chronic reflux and leads to injuring the esophageal squamous jail cell epithelium and transition to metaplastic columnar epithelium. With further injury and genetic changes, progression occurs in a metaplasia-dysplasia-adenocarcinoma sequence.

The other run a risk factors of esophageal adenocarcinoma that we volition discuss in this review include obesity, smoking, diets high in saturated fat and carmine meat, handling of Helicobacter pylori and medications that relax the esophageal sphincter. All these factors take a direct association with the increase in esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Obesity and nutrition

The risk for esophageal adenocarcinoma is associated with an increasing BMI, due to gastroesophageal reflux disease in obese individuals. Obesity is divers based on body mass index (BMI), which is a weight-to-height ratio classification that is defined every bit a person'due south weight in kilograms divided by the foursquare of their height in meters (kg/chiliad2). Obesity is a BMI greater than or equal to thirty (37). Hiatal hernias are also more common in individuals with college BMIs, which and so leads to higher adventure of reflux disease too. With the agreement of Barrett's esophagus and the transition from metaplasia-dysplasia-cancer, nosotros can see how this human relationship volition lead to college incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma with college BMI.

In addition to increased BMI, depression consumption of fruit and vegetables is an important risk factor for the evolution of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Studies take shown an changed clan betwixt fruit and vegetable consumption and esophageal adenocarcinoma. On the reverse, diets high in calories and fat have a direct association with esophageal adenocarcinoma. Diets loftier in cobweb, lutein, niacin, vitamin B6, and zinc were associated with a decreased cancer gamble (4).

Barrett's esophagus and gastroesophageal reflux illness (GERD)

More often than not, information technology is accustomed that Barrett'southward esophagus develops from GERD, and that nigh adenocarcinomas develop from chronic reflux of acidic gastric contents into the lower portion of the esophagus somewhen leading to malignant transformation at the cellular level (38). The initial intestinal metaplasia is defined as a transition of the esophageal squamous cells to tall columnar cells, which leads to a 30-fold increased gamble of an individual with Barrett's esophagus to develop esophageal cancer compared to the general population (39). In this issue, Grover et al. identified a shift in the normal esophageal microbiome in the setting of GERD or Barrett's esophagitis toward gram-negative bacterial organisms. This shift is postulated to contribute cancerous transformation to esophageal adenocarcinoma (40). Due to the moderate to high probability of Barrett'southward esophagus transforming into cancer, individuals with loftier-run a risk dysplasia require frequent endoscopic surveillance throughout their lifetime.

Individuals with GERD have the classic symptoms of heartburn and acid regurgitation, and the prevalence of the disease varies significantly amidst unlike countries (41). At that place has been a pregnant increase in the prevalence of the disease over the by decade, virtually notably in North America. The incidence of reflux symptoms within geographic areas can accomplish higher up 25% on a monthly basis, which directly parallels the rise trends in esophageal adenocarcinoma (42). Statistics show that x% of people with GERD will have underlying Barrett'south esophagus that could potentially transform into esophageal adenocarcinoma if not managed appropriately. The symptoms of GERD seem to be equally distributed among men and women, even so, men most notably accept a college incidence of complications from GERD including Barrett'due south esophagus, erosive esophagitis and esophageal adenocarcinoma (43).

Smoking and alcohol

Smoking and alcohol are known to be strong, modifiable risk factors for the development of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus, and together they accept a synergistic effect on its development. Regarding esophageal adenocarcinoma, studies accept been unable to evidence a relationship between alcohol consumption and its evolution. Nevertheless, studies have shown a straight correlation between tobacco smoking and development of esophageal adenocarcinoma, which exhibits a dose-response pattern. The risk of evolution is found to exist more than doubled and unlike squamous cell carcinoma, this risk persists even after smoking cessation (44).

Medications that relax the esophageal sphincter

Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation (TLESR) is a physiologic response of the lower esophageal sphincter to relax without swallowing. This response is triggered by gastric distension and volition initiate either the reflux of air or fluid into the esophagus, dependent on patient positioning. Fluid most frequently refluxes while in the recumbent position, while air has been noted to reflux in the upright position. TLESR is observed in normal individuals as well as individuals with GERD. Studies have been done with HRM (high resolution manometry), which have shown that the frequency of TLESR seems to be like in patients with and without GERD (45). Limited information is available regarding the duration of acid exposure to the esophagus during the episodes of TLESR. This should further be evaluated every bit the widespread apply of medications that relax the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) has raised many questions regarding the potential association with the development of esophageal cancer. The LES-relaxing effect of these drugs promotes gastroesophageal reflux disease and has been documented for various classes of medication including nitroglycerines, anticholinergics, beta-adrenergic agonists, aminophyllines, benzodiazepines, and calcium channel blockers. Every bit the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma has been rise, investigations have been washed to document any increases chance from the use of these LES-relaxing medications. Lagergren and assembly investigated the effect to determine the take chances of developing adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and an estimated incidence charge per unit ratio of 3.8 (95% CI: two.2–6.four) was found among daily, long-term users (>five years) of LES-relaxing drugs, compared with persons who had never used these drugs (46). A recent meta-analysis washed by Alexandre and associates which involved ix,412 participants showed that esophageal adenocarcinoma was strongly associated with the use of theophylline [OR ane.55, 95% confidence interval (CI): one.05–2.28; P=0.03, Itwo =0%] and anticholinergic medications (OR ane.66, 95% CI: 1.xiii–2.44; P=0.01, Iii =84%). However, calcium channel blockers and nitrates did not testify an increased clan with its development (47). As theophyllines and anticholinergics are used in the treatment of obstructive lung disease processes, this association with esophageal adenocarcinoma development warrants further investigation.

Helicobacter pylori

Helicobacter pylori is a gram-negative bacteria infecting the tum of half of the population and causing a bully bargain of gastrointestinal morbidity. The office of H. pylori in gastritis, ulceration and gastric adenocarcinoma is well established (48,49), however, the role of H. Pylori in esophageal AC is controversial. There is some testify that H. Pylori plays a role in each of the steps from GERD to Barrett's esophagus to dysplasia to esophageal Ac (50). Eradication of H. Pylori tin also reduce GERD symptoms and esophagitis in certain populations (51), thereby decreasing the likelihood of esophageal Ac. Other meta analysis show an inverse relationship betwixt H. Pylori infection and esophageal AC and propose that H. Pylori has a protective result against esophageal Air conditioning (52). In full general, it appears that data on H. Pylori and esophageal Ac is inconclusive and further studies are needed to properly constitute the relationship betwixt H. Pylori and esophageal AC whether it is protective, causal or unrelated.

Adenocarcinoma in the Asian esophageal belt

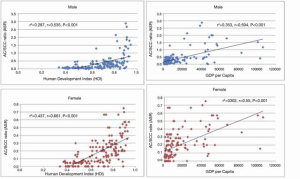

Although nosotros see the greatest increased incidence of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus in the Western countries and Northward America, Red china still contributed about xviii% of all global cases in 2012, with the "Asian chugalug" accounting for more than 30% of all cases (Figure 1) (33). In that location has been a correlation between incidence and mortality of esophageal cancer versus HDI (human development index) and Gdp per capita. The college incidence, which is SCC, is seen in lower HDI and Gross domestic product countries and the incidence of adenocarcinoma is increasing in "Western" countries, which tend to have a higher GDP and HDI (53). This correlation with HDI and GDP shows that there are socioeconomic factors related to the incidence of esophageal cancer and the areas of the China that have increased incidence of Air conditioning tend to be more developed with a college socioeconomic status (Effigy iv).

Figure 4 Relationship between the ratio of crude incidence rates of adenocarcinoma (Air conditioning): squamous prison cell carcinoma (SCC) and Human Evolution Alphabetize in male (left upper panel) and female (left lower console). Relationship between the ratio of crude incidence rates of adenocarcinoma (AC): squamous prison cell carcinoma (SCC) and Gross Domestic Product per capita in male (correct upper panel) and female person (right lower panel). HDI is divers by life expectancy, instruction, and per capita income. The ratio of AC to SCC increases equally an private's HDI and GDP per capita increases.

Prevention

As the incidence of AC of the esophagus continues to rise, a focus on prevention and screening in high-risk populations is a major global health topic. The high-risk populations should include those with chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease, older age, male person sex, obesity and family history. There is a definite recognition of the importance to eliminate global obesity with the creation of prevention programs, exercise campaigns, and diet projects. In terms of esophageal cancer as a whole, there are some policies that have been implemented regarding smoking in Western countries; however, smoking rates are not being addressed worldwide. With approximately half of all new esophageal cancer cases occurring in China, a prospective cohort protocol, National Accomplice of Esophageal Cancer- Prospective Cohort Study of Esophageal Cancer and Precancerous Lesions based on High-Adventure Population (NCEC-HRP), has been developed in Mainland china focusing on its loftier-chance rural populations—rural areas with the highest incidence of esophageal SCC. The goal of this written report is to develop a set of guidelines for esophageal cancers screening for early on diagnosis, as well as place hazard factors and develop a proper database (54). Liu et al., performed a customs-based written report that proved the effectiveness of endoscopic upper GI screening in loftier-risk populations in Red china. Their analysis proved that after a 9-yr follow up, incidence and bloodshed were lowered past 43% (standardized incidence ratio =0.57, 95% CI: 0.38–0.86) and 53% (standardized mortality ratio =0.47, 95% CI: 0.25–0.88) respectively (55). The implementation of secondary prevention programs is important, every bit cure rates for esophageal cancer are low with five-year survival rates between 10-fifteen% (56). This volition allow for identification of early on disease as currently nearly cases are being diagnosed in belatedly stages.

Determination

Esophageal cancer is frequently a lethal disease that is oft diagnosed in the late stages with a loftier mortality rate. Equally we continue to see a rise in adenocarcinoma of the esophagus, information technology is essential to implement prevention and screening policies for early on diagnosis, which will let for better chance of survival. The pattern of presentation of esophageal Air conditioning is different from that of SCC and is most likely due to different lifestyles and genetic backgrounds. As we note a correlation between the rise in adenocarcinoma and obesity, we can apply this data to implement principal and secondary prevention policies in loftier risk-populations. With implementation of these screening policies, such as screening endoscopy and lifestyle modification deportment, further studies need to be washed to decide if this will have a substantial upshot on the rates of esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Acknowledgments

Funding: None.

Provenance and Peer Review: This article was commissioned by the editorial office, Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology for the series "Global GI Malignancies". The article has undergone external peer review.

Conflicts of Involvement: All authors have completed the ICMJE uniform disclosure form (bachelor at http://dx.doi.org/10.21037/jgo-2019-gi-08). The series "Global GI Malignancies" was commissioned by the editorial function without any funding or sponsorship. John F. Gibbs served every bit the unpaid Guest Editor of the serial and serves equally an unpaid editorial lath fellow member of Journal of Gastrointestinal Oncology from Jan 2019 to Dec 2020. The authors take no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Upstanding Statement: The authors are accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accurateness or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Open Access Argument: This is an Open Admission article distributed in accordance with the Creative Eatables Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs iv.0 International License (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits the not-commercial replication and distribution of the commodity with the strict proviso that no changes or edits are fabricated and the original piece of work is properly cited (including links to both the formal publication through the relevant DOI and the license). See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/past-nc-nd/iv.0/.

References

- Thrift AP. Austerity. The epidemic of oesophageal carcinoma: Where are we now? Cancer Epidemiol 2016;41:88-95. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Patel Northward, Benipal B. Incidence of Esophageal Cancer in the United states from 2001-2015: A United States Cancer Statistics Assay of fifty States. Cureus 2018;x:e3709 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Eslick GD. Epidemiology of esophageal cancer. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2009;38:17-25. seven. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Keeney S, Bauer TL. Epidemiology of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 2006;fifteen:687-96. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Melt MB, Chow WH, Devesa SS. Oesophageal cancer incidence in the United States by race, sex, and histologic blazon, 1977-2005. Br J Cancer 2009;101:855-ix. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arnold M, Laversanne K, Morris Brown L, et al. Predicting the futurity brunt of esophageal cancer by histological subtype: International trends in incidence upwardly to 2030. Am J Gastroenterol 2017;112:1247-55. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Freedman ND, Abnet CC, Leitzmann MF, et al. A prospective written report of tobacco, alcohol, and the risk of esophageal and gastric cancer subtypes. Am J Epidemiol 2007;165:1424-33. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin JK, Hrubec Z, Blot WJ, et al. Smoking and cancer mortality among U.S. veterans: a 26-year follow-up. Int J Cancer 1995;60:190-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Carstensen JM, Pershagen One thousand, Eklund G. Mortality in relation to cigarette and pipe smoking: sixteen years' observation of 25,000 Swedish men. J Epidemiol Community Health 1987;41:166-72. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Iribarren C, Tekawa IS, Sidney S, Friedman GD. Effect of cigar smoking on the risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary affliction, and cancer in men. N Engl J Med 1999;340:1773. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Randi G, Scotti L, Bosetti C, et al. Pipe smoking and cancers of the upper digestive tract. Int J Cancer 2007;121:2049. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Wang QL, Xie SH, Li WT, et al. Smoking Abeyance and Risk of Esophageal Cancer past Histological Type: Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. J Natl Cancer Inst 2017;109: [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Thun MJ, Peto R, Lopez AD, et al. Alcohol consumption and mortality among middle-aged and elderly U.South. adults. N Engl J Med 1997;337:1705. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pandeya North, Williams K, Dark-green Ac, et al. Alcohol consumption and the risks of adenocarcinoma and squamous jail cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Gastroenterology 2009;136:1215-24, e1-ii.

- Prabhu A, Obi KO, Rubenstein JH. The synergistic effects of booze and tobacco consumption on the risk of esophageal squamous prison cell carcinoma: a meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol 2014;109:822. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Islami F, Ren JS, Taylor PR, et al. Pickled vegetables and the run a risk of oesophageal cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer 2009;101:1641. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Choi YJ, Lee DH, Han KD, et al. The relationship betwixt drinking booze and esophageal, gastric or colorectal cancer: A nationwide population-based cohort report of Republic of korea. PLoS One 2017;12:e0185778 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Pottern LM, Morris LE, Absorb WJ, et al. Esophageal cancer amongst black men in Washington, D.C. I. Booze, tobacco, and other risk factors. J Natl Cancer Inst 1981;67:777. [PubMed]

- Brown LM, Hoover R, Silverman D, et al. Excess incidence of squamous cell esophageal cancer among United states Black men: role of social class and other run a risk factors. Am J Epidemiol 2001;153:114-22. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Rafiq R, Shah IA, Bhat GA, et al. Secondhand Smoking and the Risk of Esophageal Squamous Jail cell Carcinoma in a Loftier Incidence Region, Kashmir, India: A Case-control-observational Study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e2340 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lu SH, Montesano R, Zhang MS, et al. Relevance of North-nitrosamines to esophageal cancer in China. J Cell Physiol Suppl 1986;4:51. [PubMed]

- Yang CS. Research on esophageal cancer in China: a review. Cancer Res 1980;forty:2633-44. [PubMed]

- Islami F, Poustchi H, Pourshams A, et al. A prospective written report of tea drinking temperature and gamble of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer 2020;146:xviii-25. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu J, Wang J, Leng Y, et al. Intake of fruit and vegetables and gamble of esophageal squamous prison cell carcinoma: a meta-assay of observational studies. Int J Cancer 2013;133:473. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Yang CS, Sunday Y, Yang QU, et al. Vitamin A and other deficiencies in Linxian, a high esophageal cancer incidence area in northern China. J Natl Cancer Inst 1984;73:1449-53. [PubMed]

- Abnet CC, Lai B, Qiao YL, et al. Zinc concentration in esophageal biopsy specimens measured by x-ray fluorescence and esophageal cancer risk. J Natl Cancer Inst 2005;97:301-half-dozen. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Akhtar S. Areca nut chewing and esophageal squamous-jail cell carcinoma risk in Asians: A meta-analysis of case–control studies. Cancer Causes Control 2013;24:257-65. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Muñoz Northward, Bosch FX, de Sanjosé Due south, et al. Epidemiologic classification of human papillomavirus types associated with cervical cancer. International Agency for Research on Cancer Multicenter Cervical Cancer Written report Grouping. N Engl J Med 2003;348:518-27. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zhang SK, Guo LW, Chen Q, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus 16 in esophageal cancer among the Chinese population: a systematic review and meta- analysis. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 2014;15:10143-nine. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Cancer Genome Atlas Enquiry Network. Integrated genomic label of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature 2017;541:169-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Guo L, Liu S, Zhang S, et al. Human being papillomavirus-related esophageal cancer survival: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 2016;95:e5318 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liyanage SS, Rahman B, Ridda I, et al. The aetiological role of human being papillomavirus in oesophageal squamous jail cell carcinoma: a meta-assay. PLoS Ane 2013;eight:e69238 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Arnold M, Soerjomataram I, Ferlay J, et al. Global incidence of oesophageal cancer past histological subtype in 2012. Gut 2015;64:381-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Zeng H, Zheng R, Zhang S, et al. Esophageal cancer statistics in Cathay, 2011: Estimates based on 177 cancer registries. Thorac Cancer 2016;7:232-7. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Buas MF, Vaughan TL. Epidemiology and gamble factors for gastroesophageal junction tumors: understanding the rising incidence of this disease. Semin Radiat Oncol 2013;23:3-nine. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Nelson RA, Smith DD, Schwarz RE. Nelson R.A., et al. Epidemiology and Staging of Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer. In: Morita SY, Balch CM, Klimberg V, et al. Eds. Shane Y. Morita, et al.eds. Textbook of Complex Full general Surgical Oncology New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; Available online: http://accesssurgery.mhmedical.com/content.aspx?bookid=2209§ionid=168942517.

- "Obesity and Overweight." World Health Organization, Globe Health Organisation. Available online: world wide web.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/obesity-and-overweight.

- Cameron AJ, Lomboy CT, Pera M, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction and Barrett's esophagus. Gastroenterology 1995;109:1541-6. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Hvid-Jensen F, Pedersen 50, Drewes AM, et al. Incidence of adenocarcinoma among patients with barrett'due south esophagus. Northward Engl J Med 2011;365:1375. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Grover K, Gregory S, Gibbs JF, Emenaker NJ. A discussion of the gut microbiome's development, determinants, and dysbiosis in cancers of the esophagus and stomach. J Gastrointest Oncol 2020; [Crossref]

- Eusebi LH, Ratnakumaran R, Yuan Y, et al. Global prevalence of, and take a chance factors for, gastro-oesophageal reflux symptoms: a meta-analysis. Gut 2018;67:430-xl. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Savarino E, de Bortoli N, De Cassan C, et al. The natural history of gastro-esophageal reflux disease: a comprehensive review. Dis Esophagus 2017;30:1-ix. [PubMed]

- Schneider JL, Corley DA. The Troublesome Epidemiology of Barrett's Esophagus and Esophageal Adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc Clin Due north Am 2017;27:353-64. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gammon Md, Schoenberg JB, Ahsan H, et al. Tobacco, alcohol and socioeconomic status and adenocarcinomas of the esophagus and gastric cardi. J Natl Cancer Inst 1997;89:1277-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Han SH, Hong SJ. Transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation and the related esophageal motor activities. Korean J Gastroenterol 2012;59:205-x. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Lagergren J, Bergstrom R, Adami HO, et al. Association between medications that relax the LES and chance for esophageal adenocarcinoma. Ann Intern Med 2000;133:165-75. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Alexandre L, Broughton T, Loke Y, et al. Meta-analysis: risk of esophageal adenocarcinoma with medications which relax the lower esophageal sphincter. Dis Esophagus 2012;25:535-44. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Blaser MJ, Perez-Perez GI, Kleanthous H, et al. Infection with Helicobacter pylori strains possessing cagA is associated with an increased risk of developing adenocarcinoma of the stomach. Cancer Res 1995;55:2111-5. [PubMed]

- Lanas A, Chan FKL. Peptic ulcer illness. Lancet 2017;390:613-24. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kountouras J, Chatzopoulos D, Zavos C, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection might contribute to esophageal adenocarcinoma progress in subpopulations with gastroesophageal reflux disease and Barrett'southward esophagus. Helicobacter 2012;17:402-3. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Kountouras J, Zavos C, Chatzopoulos D, et al. Helicobacter pylori and gastro-oesophageal reflux affliction. Lancet 2006;368:986. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Polyzos SA, Zeglinas C, Artemaki F, et al. Helicobacter pylori infection and esophageal adenocarcinoma: a review and a personal view. Ann Gastroenterol 2018;31:viii-13. [PubMed]

- Wong MCS, Hamilton Due west, Whiteman DC, et al. Global Incidence and mortality of oesophageal cancer and their correlation with socioeconomic indicators temporal patterns and trends in 41 countries. Sci Rep 2018;viii:4522. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Chen R, Ma S, Guan C, et al. The National Cohort of Esophageal Cancer-Prospective Cohort Study of Esophageal Cancer and Precancerous Lesions based on High-Risk Population in Prc (NCEC-HRP): study protocol. BMJ Open up 2019;9:e027360 [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Liu G, He Z, Guo C, et al. Effectiveness of Intensive Endoscopic Screening for Esophageal Cancer in China: A Community-Based Study. Am J Epidemiol 2019;188:776-84. [Crossref] [PubMed]

- Gibbs JF, Rajput A, Chadha KS, et al. The changing contour of esophageal cancer presentation and its implication for diagnosis. J Natl Med Assoc 2007;99:620-6. [PubMed]

Cite this article as: Grille VJ, Campbell S, Gibbs JF, Bauer TL. Esophageal cancer: the ascent of adenocarcinoma over squamous cell carcinoma in the Asian belt. J Gastrointest Oncol 2021;12(Suppl 2):S339-S349. doi: 10.21037/jgo-2019-gi-08

robertsfrasmils54.blogspot.com

Source: https://jgo.amegroups.com/article/view/45330/html

0 Response to "Esophageal Cancer in the United States Social Class Peer Reviewed"

Post a Comment